Raising the Bar: How Revenue Expectations at Series A Are Quietly Climbing

Beyond the $1M Myth: Real Numbers from 9,000 Deals

For years, a familiar benchmark has shaped early-stage fundraising: hit $1 million in Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR), and you're ready to raise a Series A.

It’s a simple heuristic—one that’s embedded in pitch conversations, investor panels, and founder playbooks. Since ARR is typically used as a proxy for near-term revenue (i.e., $1M in ARR today suggests ~$1M in revenue over the next 12 months), this rule of thumb implied that most Series A companies were actually earning less than $1 million at the time of their raise.

But that rule may be outdated.

While much has changed in the venture landscape—including the rise of generative AI, broader market correction cycles, and a shift toward more disciplined investing—this $1M ARR benchmark has remained remarkably persistent. My intuition, however, suggested that Series A rounds were now going to companies with more traction. So I dug into the data.

What the Data Says

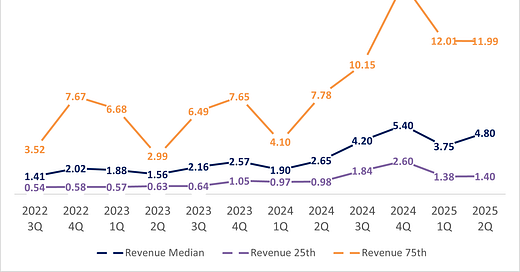

I reviewed over 9,000 Series A deals in Pitchbook from the past three years, filtering for those that included revenue reported near the time of the raise. The results confirm what many investors and founders may already be sensing: revenue expectations are increasing.

The median revenue at Series A has risen steadily since 2022, with only minor fluctuations. In the most recent quarter, the median stood at $4.8 million.

Even the bottom quartile has climbed above the traditional $1 million ARR threshold.

The top quartile has seen the most dramatic rise—jumping from low single digits to low double-digit millions in revenue.

Because Pitchbook doesn’t track ARR specifically, these figures likely underestimate the actual forward-looking revenue metrics used by investors. In other words, many companies may be raising their Series A rounds with ARR well above $5 million.

Similarly, I ran the figures on pre- and post-money valuations for Series A companies (again, only where they reported corresponding revenue figures) as well as calculated the median valuation to revenue multiple.

The general trend over the past few years has been a steadily increasing valuation.

Interestingly, and probably due to outliers in the data, the valuation to revenue multiple is fairly consistent, typically ranging from 9 to the low teens.

Valuations Are Up—But So Is Revenue

I also looked at pre- and post-money valuations for these same Series A companies and calculated valuation-to-revenue multiples. As expected:

Valuations have trended upward over the same period.

Valuation multiples have remained relatively stable, ranging from ~9x to the low teens.

This suggests that investors aren't necessarily paying more per dollar of revenue—they’re just backing companies with more commercial traction. It's a shift in stage expectations, not pricing discipline.

What This Means for Founders

If you're a founder building toward a Series A, here’s the takeaway: investors are looking for more than they used to.

The bar has risen—not astronomically, but meaningfully. And while every company is unique, you should be prepared to justify why you're raising now rather than waiting to grow revenue further.

Three practical tips:

Benchmark yourself early – Compare your revenue to recent Series A deals in your sector. Don’t rely on outdated rules of thumb.

Frame your traction wisely – If you’re below the new norms, articulate a compelling growth narrative or product-market fit story.

Use this data strategically – Revenue expectations don’t just shape investor meetings—they can also guide when to launch pilots, hire sales teams, or time your next funding push.

Implications for CVC Professionals

For corporate investors, this trend is equally important. It means that by the time a startup hits Series A, it may already have significant revenue—and possibly, meaningful market validation. That’s a positive signal for commercial partnerships, co-development opportunities, or even downstream acquisitions.

But it also raises the stakes. If you're only engaging with startups once they’ve hit these higher revenue milestones, you may be arriving late to influence roadmap decisions or shape early integrations.

CVCs should consider:

Tracking startups earlier in the funnel—especially pre-Series A—before valuation inflection points.

Updating internal investment criteria to reflect the revenue realities of today’s Series A landscape.

Advising portfolio companies on the shifting benchmarks so they can better prepare for external funding.

Final Thoughts

The Series A landscape is evolving. Founders and investors alike need to recalibrate their expectations and strategies. The old $1M ARR benchmark was useful in its time—but today’s market demands a more nuanced understanding of traction and timing.

It's also worth noting that ARR itself is becoming a less reliable north star—particularly for AI-native startups. Many monetize through usage-based pricing or API consumption, not fixed contracts. This makes ARR a lagging or misleading metric in many cases. As I argue in New Rules for New Models: Beyond ARR in the AI Era, AI startups often show meaningful progress through pilots, technical adoption, or deep enterprise integration—long before ARR materializes. Investors and founders should consider complementary metrics that reflect the true value and traction of emerging technologies.

The good news? With better data and sharper awareness, both startups and CVCs can navigate this shift with confidence.